Excerpts from the Book

From Chapter 2: The Jim Crow Era and My Family

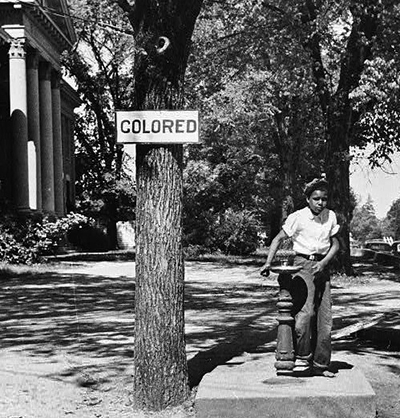

“Colored” drinking fountain on the county courthouse lawn, Halifax, N.C., 1938. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsc-00216 (P&P)

“Colored” drinking fountain on the county courthouse lawn, Halifax, N.C., 1938. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsc-00216 (P&P)

Colonel William Henry FitzGerald was my mother’s grandfather on her paternal side. Like Jerry Robinson [her maternal grandfather], he had owned slaves and fought in the Civil War. Also, like Jerry, he lived to see the entrenchment of what became known as the Jim Crow era, characterized by a reassertion of the white supremacy that had existed during slavery. During this time period, Colonel FitzGerald was a Tallahatchie County supervisor, a Mississippi state senator, and a judge.

In the style of the old plantation South, my mother and her older sister had a black “mammy,” Margaret, a former slave who helped raise them, perhaps even functioning as their surrogate mother.

I grew up in all-white neighborhoods in Norfolk, Virginia, went to an all-white church, was part of an all-white Boy Scout troop, and went to essentially all-white schools.

From Chapter 3: My Mother’s Legacy

Studio photograph of Bill’s mother in the spring of 1964, near the time of Bill’s graduation from military high school.

Studio photograph of Bill’s mother in the spring of 1964, near the time of Bill’s graduation from military high school.

More than anyone else, my mother taught me to have racist views. She told me on many occasions that blacks were inferior to whites, and she modeled racist behavior in many ways. Because of my closeness to her, I accepted her beliefs as my own.

I remember one time when I was about twelve riding with my mother in her Ford through the streets of Norfolk, Virginia. We stopped at an intersection where Mom noticed two or three black men in the neighborhood. Immediately she locked all the car doors before continuing the drive.

My mother led me to believe that black people were not clean and were subject to unmentionable diseases. I came to think, as she did, that one should avoid touching black people if at all possible and that the prudent thing to do, if that was not possible, was to wash one’s hands afterwards. I believed that black people had an offensive smell, and I would hold my breath when I walked past them.

My mother had grown up in Mississippi with separate facilities for black people. In the home of my teenage years, we had a separate, less furnished bathroom located by the back door for the black maids. My mother would not have been comfortable with them using the bathrooms we used .

In my twenties, when I began to disagree with my mother’s view that black people were inferior, she would say, “Son, you just don’t understand.” All of the teachings and experiences of her childhood and youth had firmly convinced her of her position and, as far as I could tell, she never examined or questioned it.

I remember one time when I was about twelve riding with my mother in her Ford through the streets of Norfolk, Virginia. We stopped at an intersection where Mom noticed two or three black men in the neighborhood. Immediately she locked all the car doors before continuing the drive.

My mother led me to believe that black people were not clean and were subject to unmentionable diseases. I came to think, as she did, that one should avoid touching black people if at all possible and that the prudent thing to do, if that was not possible, was to wash one’s hands afterwards. I believed that black people had an offensive smell, and I would hold my breath when I walked past them.

My mother had grown up in Mississippi with separate facilities for black people. In the home of my teenage years, we had a separate, less furnished bathroom located by the back door for the black maids. My mother would not have been comfortable with them using the bathrooms we used .

In my twenties, when I began to disagree with my mother’s view that black people were inferior, she would say, “Son, you just don’t understand.” All of the teachings and experiences of her childhood and youth had firmly convinced her of her position and, as far as I could tell, she never examined or questioned it.

From Chapter 9: Significant Experiences Along the Way

Bill Drake in his early 20s.

Bill Drake in his early 20s.

For the first time in my life I was involved in communities that included a lot of black people. My interaction with them was extremely educational for me . As well as learning to see black people as human beings with positive and negative aspects just like any other people, I became more aware of the residues of racism that I still carried

After working for many years to overcome racism within myself, I felt an obligation to help overcome it in the world around me, and writing such letters-to-the-editor was one way to do that. It also gave me an opportunity to learn more about King and the civil rights movement.

My most significant letter was published on January 19, 1998, Martin Luther King Day. It was a letter apologizing to black people, especially those who live in my hometown of Norfolk, for the racist actions of my youth. I had thought about writing such a letter for months and was grateful to have an opportunity to express regret for my past. The letter simultaneously appeared as a guest editorial in The Virginian Pilot in Norfolk, The Union in Grass Valley, California, and the San Francisco Chronicle.

Dear Editor,

This is a letter of apology to the African-American community of Norfolk, Virginia.

I am a 52-year-old white male who grew up in Norfolk. My parents were from the Deep South, and my great-great-grandparents, on my mother’s side, owned 150 to 200 slaves on the Mississippi delta.

I wasn’t a mean kid, but as a child I adopted the racist views of my family and the white community I grew up in. Such views, at least in my family, were passed on from generation to generation. I grew up hearing the adult black men who worked for my grandfather referred to as “niggers” behind their backs. When my mom and I drove downtown, if we saw black males, my mother locked the car doors out of concern for our safety, which led me to believe there was something to fear.

I learned from my family and peers to believe that blacks were naturally inferior to, and less intelligent than, whites. If I walked past a black person, I held my breath because I thought black people were supposed to smell bad. If I touched a black person, I would have wanted to wash my hands to avoid getting a disease. I did these things not to intentionally degrade blacks but because of what I had learned to believe about them. Living in a segregated world, with rules that regulated black and white relationships, I had no personal experiences to counteract the myths.

I deeply regret the racist attitudes I personally held in the past and which I have worked hard to overcome. Also, and more specifically, I offer my apology to African-Americans, especially those in Norfolk, for the misdeeds I committed as a teenager to gain approval from my peers and inflate a false sense of self-worth. On several occasions I telephoned black people’s homes in Norfolk to try to imitate a “black voice” and invite blacks to an imaginary NAACP meeting. One evening a friend and I drove through a black neighborhood and shouted derogatory names. These misbehaviors added to the millions of other degrading experiences blacks and other minorities have experienced from fellow Americans.

Because my family had racist views did not mean that we were bad people. My parents were not prejudiced against blacks because they wanted to be cruel but because of deeply held beliefs that they were convinced were true.

A turning point came for me when I was 17, watching a white teenager on a bus kicking the back of a black woman’s seat just to annoy her. Although I did not say anything, his action seemed senseless and cruel. About a year later, out of the blue, I asked my older brother, “Fletcher, does it really make sense to look down on people because they are a different color from us?” His response was simply, “No.” That was the entire conversation, but it changed my life, and during my college years I became a supporter of civil rights. My first relationships with African-Americans, as a teacher in Cleveland, completed the shattering of the myths I had learned.

Racist attitudes held by our family and others were tragic for many reasons. They perpetuated myths. They resulted in actions that caused other human beings pain, that encouraged them to doubt their potential and self-worth, and that denied them basic human rights. And, as Martin Luther King said, racism not only keeps the victims from being all they can be, it also keeps the perpetrators of racism from being all they can be. Racism prevents the racist from opening his or her heart to love all of the Creator’s children and from being a whole human being.

As human beings we tend to have prejudices and insecurities, and if we want to create a more loving, peaceful, and just world, those of us that have prejudices have to acknowledge them and work to overcome them. We also need to do our best to extend the healing power of love to all people, whether we like them and their beliefs and actions or not.

Racism still exists in the institutions and individuals of our society, but I hope that we are coming a little closer to realizing King’s dream— that someday people will be judged by their character rather than their color and descendents of slaves and slave owners will be able to come together in friendship.

Bill Drake

After working for many years to overcome racism within myself, I felt an obligation to help overcome it in the world around me, and writing such letters-to-the-editor was one way to do that. It also gave me an opportunity to learn more about King and the civil rights movement.

My most significant letter was published on January 19, 1998, Martin Luther King Day. It was a letter apologizing to black people, especially those who live in my hometown of Norfolk, for the racist actions of my youth. I had thought about writing such a letter for months and was grateful to have an opportunity to express regret for my past. The letter simultaneously appeared as a guest editorial in The Virginian Pilot in Norfolk, The Union in Grass Valley, California, and the San Francisco Chronicle.

Dear Editor,

This is a letter of apology to the African-American community of Norfolk, Virginia.

I am a 52-year-old white male who grew up in Norfolk. My parents were from the Deep South, and my great-great-grandparents, on my mother’s side, owned 150 to 200 slaves on the Mississippi delta.

I wasn’t a mean kid, but as a child I adopted the racist views of my family and the white community I grew up in. Such views, at least in my family, were passed on from generation to generation. I grew up hearing the adult black men who worked for my grandfather referred to as “niggers” behind their backs. When my mom and I drove downtown, if we saw black males, my mother locked the car doors out of concern for our safety, which led me to believe there was something to fear.

I learned from my family and peers to believe that blacks were naturally inferior to, and less intelligent than, whites. If I walked past a black person, I held my breath because I thought black people were supposed to smell bad. If I touched a black person, I would have wanted to wash my hands to avoid getting a disease. I did these things not to intentionally degrade blacks but because of what I had learned to believe about them. Living in a segregated world, with rules that regulated black and white relationships, I had no personal experiences to counteract the myths.

I deeply regret the racist attitudes I personally held in the past and which I have worked hard to overcome. Also, and more specifically, I offer my apology to African-Americans, especially those in Norfolk, for the misdeeds I committed as a teenager to gain approval from my peers and inflate a false sense of self-worth. On several occasions I telephoned black people’s homes in Norfolk to try to imitate a “black voice” and invite blacks to an imaginary NAACP meeting. One evening a friend and I drove through a black neighborhood and shouted derogatory names. These misbehaviors added to the millions of other degrading experiences blacks and other minorities have experienced from fellow Americans.

Because my family had racist views did not mean that we were bad people. My parents were not prejudiced against blacks because they wanted to be cruel but because of deeply held beliefs that they were convinced were true.

A turning point came for me when I was 17, watching a white teenager on a bus kicking the back of a black woman’s seat just to annoy her. Although I did not say anything, his action seemed senseless and cruel. About a year later, out of the blue, I asked my older brother, “Fletcher, does it really make sense to look down on people because they are a different color from us?” His response was simply, “No.” That was the entire conversation, but it changed my life, and during my college years I became a supporter of civil rights. My first relationships with African-Americans, as a teacher in Cleveland, completed the shattering of the myths I had learned.

Racist attitudes held by our family and others were tragic for many reasons. They perpetuated myths. They resulted in actions that caused other human beings pain, that encouraged them to doubt their potential and self-worth, and that denied them basic human rights. And, as Martin Luther King said, racism not only keeps the victims from being all they can be, it also keeps the perpetrators of racism from being all they can be. Racism prevents the racist from opening his or her heart to love all of the Creator’s children and from being a whole human being.

As human beings we tend to have prejudices and insecurities, and if we want to create a more loving, peaceful, and just world, those of us that have prejudices have to acknowledge them and work to overcome them. We also need to do our best to extend the healing power of love to all people, whether we like them and their beliefs and actions or not.

Racism still exists in the institutions and individuals of our society, but I hope that we are coming a little closer to realizing King’s dream— that someday people will be judged by their character rather than their color and descendents of slaves and slave owners will be able to come together in friendship.

Bill Drake

From Ch. 11: Some Causes and Effects of Racism and Other Forms of Prejudice

Section 1: Learned Prejudice

My childhood conditioning was so thorough that I still have emotional reactions that are racist even though I rejected racism on an intellectual level several decades ago. The following poem was the result of such a reaction.

My childhood conditioning was so thorough that I still have emotional reactions that are racist even though I rejected racism on an intellectual level several decades ago. The following poem was the result of such a reaction.

A Handshake

I wince

slightly,

ever so slightly,

and I feel

mixed feelings,

as I shake your hand.

My mind has broken

the chains

of my past,

and I know it’s ok

to shake your hand.

But the emotional conditioning

of my childhood

sends some small part of my psyche

to the store

to look for disinfectant.

While once again

I feel the pain,

the lifelong pain,

the wretched pain,

from the

almost hereditary

teachings

of my southern

boyhood home.

slightly,

ever so slightly,

and I feel

mixed feelings,

as I shake your hand.

My mind has broken

the chains

of my past,

and I know it’s ok

to shake your hand.

But the emotional conditioning

of my childhood

sends some small part of my psyche

to the store

to look for disinfectant.

While once again

I feel the pain,

the lifelong pain,

the wretched pain,

from the

almost hereditary

teachings

of my southern

boyhood home.

Shortly before my fifty-third birthday in July of 1998 I wrote this poem. My wife and I were in a grocery store when I met a black acquaintance whom I had not seen in a few years. I enjoyed seeing someone I knew and liked, and it was nice to briefly catch up on the changes in our lives. But when we shook hands, I noticed a subtle emotional reaction, a very slight discomfort within myself at touching a black person. It was as if “some small part of my psyche [went] to the store to look for a disinfectant.” The experience was very painful. I was saddened that such conditioning was still with me after all these years, and that it would probably always be with me to some degree. (Yet I also realized that I must do my best to accept and love myself as I am and not feel guilty about this part of myself, while continuing to work to overcome it.)

From Ch. 12, Section 3: Becoming Aware of and Examining Our Judgments and Stories about Others

There are many times that I have observed that a judgment I have of another person is true, at least to some degree, of myself (whether or not it is actually true of the other person). This has helped me soften my criticisms of others. For example, if I think of the racism my Mississippi cousins exhibited, or I am upset about someone’s racist behavior in the present, when I remember the racism that I too demonstrated in my youth and recognize that even today I have prejudices and traces of racism, my judgments are weakened.

From Ch. 12, Section 4: Overcoming Self-Righteousness

If I am boycotting or demonstrating against a company that discriminates against black people (as civil rights workers often did in the late 1950s and 1960s), it is important for me to remember that I constantly have prejudices against various people and often feel the separateness from others that creates the feeling of “us versus them.” This human tendency that I so often see in myself is not unrelated to what the company is doing when it discriminates against blacks. That which I oppose outside of myself can often be found within me. This realization inspires me to follow through on the protest, boycott, or whatever action I am taking with less self-righteousness and heightened compassion and honesty.

From Ch. 12, Healing Racism and Prejudice in Ourselves

If we want to heal society of racism and prejudice, the most important place to start is with ourselves, for we ourselves are the people we most have the ability to change. As we diminish our own prejudices and racism and become more accepting and loving people, we affect those around us in a more positive way, which in itself makes a powerful contribution to the world. As we grow to be more loving and less judgmental, our work to effect social change is likely to be more successful, and we are less likely to contribute anger and hatred to a world that is already too full of both.

From Ch. 12, Section 8: Honoring Diversity

While our “sameness” transcends, and is always greater than, our “differentness,” and seeing how we are all alike can diminish the barriers between ourselves and others, it is very important to respect the unique cultures and experiences pertaining to people of other races and cultures.